"emberwall" is a short story about kinship, time, and loss, with elements of magical [sur]realism and nonlinear narrative.

guiding questions // clues for the curious:

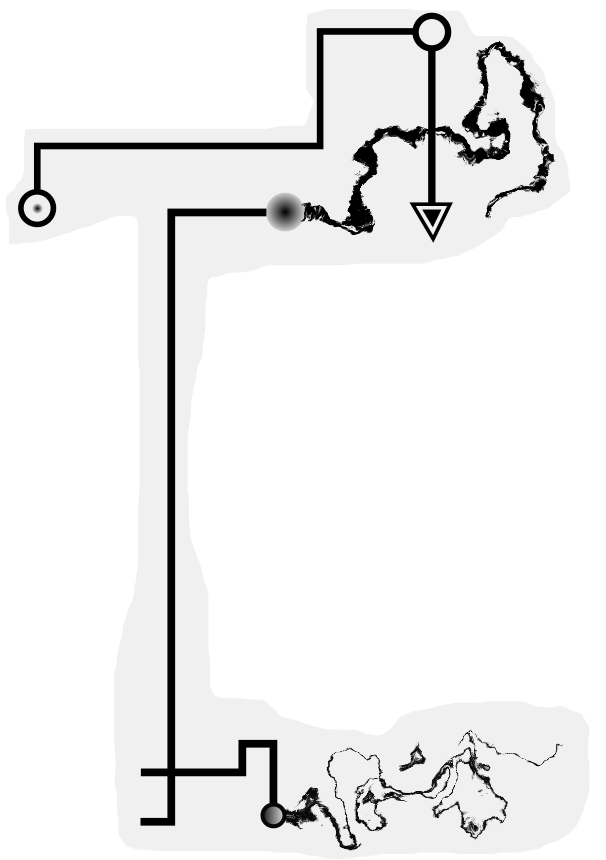

- the story is divided into two parts. how are they connected, and which comes first? why might this be? how is this related to the protagonist's goals and actions?

- → → → pay attention to the arrows. ← ← ←

- geometry is important. there are four characters and two directions, but ari's ritual is triangular: "the secret," he tells us, "was in three, not in infinite, points." for whom is it intended? who winds up affected?

- consider the tale of the sun dial of ahaz from the old testament, which ari incorporates into his experiments: it is a crucial intertext.

- consider the role of eyes, perception, and perspective. who or what sees the fullest range of narrative events? where do the characters, and the reader, stand in this regard?

- consider flames: candles, beacons, charcoal. what is an "emberwall"?

- for extra fun, feed the text to the word scrambler and read the warped version instead.

emberwall

II

A flickering, a flickering. Energy surged; it flitted in pathways through wires from bulb to socket to circuit. In the faint glow one could make out the sheets of paper, several of them, spread across the floor, tacked onto the walls in no cohesive order. Energy surged. Hood draped over his head, demented friar, Ari crouched over the desk, blotting. Beginning at the top of each sheet, he scratched the pen side to side, each word made illegible. Now and then he held it down and let the ink seep into the sheet and onto the desk. An excess within needed to overflow, to spill elsewhere. No one needed to read his thoughts, to squander their efforts. It would never synchronize properly. Sheet after sheet, then onto the notebooks, fetched sporadically from the carpet, blotting.

He did not understand what had compelled him to devote a life to researching and writing, to attempt to invoke some deep-rooted significance from an existence which certainly lacked that which certainly was a slow motion decay several motions of which he had yearned to halt distill and alchemize. Every book in the best library would boast only black ink on black pages so the eyes would not strain more than necessary which if they must do so at all was more than necessary. Reading is decoding is scrutinizing is not necessary so blot it out black it out and for god's sakes have it over with. If you must print books print black on black and save the populace the strain the mind does not need to be bothered so. Thoughts are ephemeral so write them down so they do not remain so but the mind's sparks are ephemeral too and it's all so confounding and circular and so erase and scratch and cross out the symbols.

These books in particular needed to be blotted for the sake of Ari's reputation and protection. He had found the research groundbreaking and very much necessary in order for him to reach into the vortex and yank out something substantial and he did not know this but all he had done was regress not reverse was undo not redo. He had meticulously crafted a tapestry but now had come time to unravel the strings. It was hard to imagine who among his colleagues at the university and companions elsewhere would approve of the writings and the final action they suggested.

His hands shook incessantly. And so he crossed out the characters.

He came across the last page of the last notebook. The illustration: an inverted equilateral triangle; writing along the edges; a vertical eye in the center; above, the scribbled ignition. Other variations with different shapes and starting points for the words had been inscribed elsewhere on the page, but were now crossed out. Ari found himself staring at the eye in the triangle and it stared back and he blinked and it didn't. Its reach beyond his, a godly perception beyond the flesh here immortalized, yet his pen had etched it. A transient sense of purity. What had he meant? If he hadn't defaced the previous pages he would know. Something within seemed to know he could know but lied to him and said there's no point there's no point erase damn it erase.

Air rippled through the room almost imperceptibly but it did not follow the expected flow; it seemed to branch out in random currents in random zones and Ari was still staring into the eye on the page. If it would only blink and acknowledge and subsequently envelop him but it wouldn't it was not his and he could not will it and its inscribed being enthralled and surpassed him and he stared and did it stare no only he stared. Without deciding he decided to leave the image untarnished.

← ← ←

Lucas sat in the twilight on the couch with the needle in his arm, the one that would always be there at some point or another. The gaps between his molecules were vast and unassuming, forming the loosest parameters of a complete mind. Watermelon-like, the cells served only to hold the liquids vaguely in place. His fluid had yet to congeal, and in its vulnerable turbulence dribbled from him and down the chins of others. It was imperative that he condense, and do so at once. Once solidified he would come to know the defiance that is the birthright of all autonomous things.

But would these thousand spirits gain entrance to the celestial realm wherein lay, coveted and luminous, the uniform self? Could he synthesize the shards without the aid of a needle? What was buried could not be exhumed, even by him it ensnared, not in any literal vulgar way nor by any other method. His old pal had tried with his pen. Had tried to offer him another go at their kinship and his outlook. It was for him the dial most needed reversal, but it was he who had been left behind by the blood, hers not his, in that accursed tri-tipped image—left before and after only with the needles, bittersweet friends, keys to that dazzling galaxy within his arms.

← ← ←

Hers not his. The sound seemed to bounce from the air around her into the doorbell as she pressed it. The ringing had been emanating in the hallway beforehand, reverberating in the musky air. Then pulled like a vacuum into the button and the silence upon pressing. As it were, Julianne Porter stood oblivious to this, gaze unfocused on the door. Everything was periphery everything particles first miniscule then wider until they overtook anything in the foreground. Feet shuffling and then door opening and Ari there looking and him goddamn it what do I have to do now this visit can only create how do I erase.

Can I come in? Yes.

Ari walked away and sat on the couch and Julianne closed the door and the sound of silence at the wrong time again not what you'd expect and neither noticed. Julianne sat across from him and there were a great many blotted pages everywhere.

Ari, can we talk? Yes.

I need your help.

Neither was looking at the other or in front of them or at anything else and what else was there. He made no reply.

Another publication fell through. No reply. I'm at wit's end here. No reply. It seemed as though words might have come out but she wasn't sure, like they had but had been sucked back in but she hadn't been able to catch them like if the mouth moved it was all quiet and if it didn't there might have been something but she couldn't be sure. She tried again.

I'm not asking for money or anything. Can you just read over my manuscript again?

The intonations did not synchronize properly with the motions of either set of lips.

No. Why not? Because I can only tear down, not upraise. What do you mean? Why, look at the floor.

So she strained her eyes to exit the peripheral glaze and see minute forms so she noticed the words all scratched out and desynchronization over and over again which did not mean a thing and she did not grasp it on the most conscious level but something submerged shook and rattled and growled at the sight of what had divorced them all from each other and from themselves. She might have pleaded further but the space between her and the submerged was too deep. It was useless and he wouldn't change his mind and the submerged Julianne touched that without really transmitting it to her and without volition the legs stood up and crossed the room and the being inside if you could call it that did not think or decide.

Goodbye Ari. And again the sound that failed to correlate properly and again that no one noticed.

← ← ←

Like a faulty windshield wiper glazing debris along a windowpane, the junk smeared across his vision. The glaze was uneven, leaving little pockets of high definition peppered occasionally throughout. Julianne stood there before him in mostly sepia tones. Her once upright figure stood slumped and haggard. The wrists that always snapped into motion behind the keyboard were no longer limber; they dangled like worms at the sides of her dirty sweatpants. How could she have altered so drastically in so brief a period of time? What compelled her to suddenly come by so frequently, without judgment or condescension? She lacked the proper marks from using, especially on one with such delicate, pristine skin. Lucas knew this all too well. It wasn't drugs. Perhaps it was a death. Perhaps he could get it out of her this time, if he could emerge from his own murk to begin with. And so.

Are you sure you don't want to sit down? I wouldn't say that. So you do want to then? Nor that.

Suit yourself.

Lucas watched her look into the air and then across the floor, every so often stealing a glance at him, holding it for an instant without nervousness or concern, then sinking back into her own wiggling domain. She served merely as the point into which objects reflected their existence, a static ephemeral thing next to their perhaps undeniable solidity. Radical idealists held that the existence of physical objects was contingent upon the mind of an observer, that if the sensory perception of said mind were to be removed, the external would disappear completely. With Julianne it seemed quite the opposite; if the masses enveloping her were to retreat, even momentarily, she would recoil backwards and inwards into a patch of air.

Lucas thought she might slip imperceptibly into a shadow cast by the wall and it made him uneasy. The unease made him not quite but almost lucid. He strained his eyes to see her. He was sober and her outlines were shaking and the wall behind her wiggled. Little dots of static wiggling about the expanse that held her, ever so tenuously, intact. Embers blazing side by side fusing to erect a facade but they could not and then only chunks of wiggling hellish charcoal.

What's happened to you, Julie? I can't… I can't say. Yes, you can.

A long silence, then faintly. No.

Spit it out. Why are you here if you don't want to talk? I don't know… why I'm here. Pause. I don't know… what's happened… to me.

Did someone die? No… I don't think so… I can't remember.

You'd remember.

The faintest, faintest flicker of recognition on the outlines of her eyelids.

Did I die? No, you're still here. Were things different before?

Not for me, but for you, much different. But how can you not know? Did you take something? Did I take something? A drug I mean. A needle… here. I mean did you take something else with someone else. Not that time with me.

Slowly thinking, then saying. If I said I had taken something, would that be an explanation? It might.

I want to say so, then. But I don't believe I did… I don't believe.

Was it with Ari?

It was the first Lucas mentioned of him in years, but it didn't faze Julianne. Ari… I don't think so. I didn't take anything, I don't think… Ari. But he's the same as me.

The same as you? How? Yes. The same as me.

Ari had not, as long as they had been friends, dabbled with substances. It was unlikely he would now. He relented. He could not assess the situation. The fissure between them could not be bridged, the two obscured by distinct forces: his hazy sepia, her rippling outlines. He knew she was lost. How it came to be did not matter. The rigid woodpole she had spent her life constructing had been hacked down, down, woodchips thudding onto the floor, a nebulous shaking outline in its place. It was not that the real Julianne Porter had been marginalized somewhere within the frame of those jittering lines, but that her very selfhood had been extinguished, swallowed up quietly and entirely. She stood there before him, rippling.

Lucas did not know what to say or do. She, the writer, even less so than he. Like the candle, the highest tip had been ignited, the fuel and energy sparked and used. This slow burning could only bring about one end: what was once a beacon would thereupon be a wax puddle, misshapen, pale and indicative of its prior state only in form, never in spirit.

← ← ←

The figures excised from the last scrapbook still sat in the kitchen trashcan, removed from the memories and buried beneath browning banana peels and damp coffee filters. It was as though they, the heaps of trash, were endowed with endless value and the spaces around them, shiny and pristine, were meritless by contrast. The scraps had not been cut out of photographs; photographs had formed around those empty spaces. Janis Hudson excavated these figures, exhuming a dozen Janises from their resting places, smiling or sitting or cooing, and placed them on the kitchen counter. Hello to you too. And you and you. Why were you abandoned so, little selves? To hell with that, and to hell with them all. She found herself transfixed by the figures, each an instance of her youthful radiance, each a projected self, a direction she could move in and embody, each a fresh, vivacious, beautiful little thing, ready to engage and love and proliferate.

Transfixed by the figures. Their dark eyes gentle and cheeks faintly shaded, rose-like. It was good that she had separated them from the rest, the non-Janises. She did not need them. Why bemoan the absence of those who clearly lacked commitment, who did not understand devotion? She would make a new set of scrapbooks, and these would counter the others. As for the others, she wouldn't keep them. They were to be tossed. After all, who had ever wanted them? Her husband had disappeared without a word. Her son with his absurd theories and his inscrutable nonsense all the damn time. No, this new series would feature only her, darling, loveable Janis, a testament to her will and success. At the pinnacle of these reflections, her phone rang; the words slid quietly atop the pile of voice messages she hadn't and wouldn't listen to. Complacency and joy the same, inextricable to the subject for whom they hold.

In the bathroom, she gazed longingly at herself in the mirror. No longer the miniatures but the real thing in its supposedly three dimensional glory. Or she thought she gazed at herself but in fact the mirror gazed at her, projecting her flatter-than-she-thought image from the glass onto the linoleum in front of it. A projection of herself, of beauty, of confidence. Traits that she lacked before but had suddenly, inexplicably acquired, as if through chemical or ritualistic means.

As if through chemical or ritualistic means. She applied the foundation as usual, then the lipstick and eyeliner normally reserved for special occasions. And why not? If beauty can be augmented, from gorgeous to glorious, why thwart that? Her heels clomped across the living room floor and over to the door, body in pursuit of legs. Her clothes were tight and revealing and she did not think of herself as a mother, even a member of society, subservient to no entity other than glory, clomping and turning deeply interested heads. She would go into the city and meet someone. And why not?

← ← ←

The eye had something of a conscience and so it deemed that she could know; this information might need an alternate form, an illusion or distortion perhaps, but she would know regardless.

Things were not always this way an inkling pervaded Julianne that there had been somewhere a prenatal existence somewhere in the surrounding static wind she had been searching for an envoy who would inform remind save but he was not there or elsewhere and it all sloshed about in the ether disparate points beertop foam swirling in the dried engravings of her cerebral cortex almost thoughts almost. Something had pulled her apart from herself had taken the individual segments of her persona threaded together so tightly to form a core and pulled the thread and some pieces remained but others permanently lost and those that remained were not in the right order were out of synch like the sounds and words and lights and wind about her.

The rippling outlines solidified temporarily, unified enough to form a sensation like determination, a sensation that propelled her to at least comprehend what she knew she could not amend. She had willed the fragments to pull together briefly—it had to be so, they could not hold long—to grasp the predicament, the nature of her curse. It was all she had left of her bygone mentality, to analyze and open portals, to scrutinize to the third degree, knowledge that she knew would not yield change, but was a form of knowledge, an innate and not an instrumental desire, valuable in itself even if she remained stuck.

It was for these reasons she stood in the hallway outside Ari's apartment, there during the Philosophy course he instructed, there with the ringing that sounded when the bell wasn't being pushed but lapsed into an uncomfortable silence when it was. But she would not press it today, and if she had he wouldn't be present to open the door regardless, he had not spoken to her since her last visit but she had checked the department's website, easy enough to discover the proper time but the method hadn't come to her yet. But it would, she knew. She would literalize the fragmentation of her core to disperse and seep and seep she did the pieces became dots the whole loosened it was only conjoined through the faintest remainder of a will so if she allowed her concentration to lapse it all would follow shred dissipate seep into the deep ridges alongside and underneath the doorway through the minute openings feeling and perceiving nothing cognition and selfhood relinquished.

Then Julianne or something akin to that on the other side of the door. Molecules in their conventional place now to investigate and comprehend. She strode slowly to Ari's study and began perusing the papers strewn on the floor, on the desk, tacked up onto the walls. Everything blacked out scratched vehemently thoroughly not a word to be gleaned. Every ripped sheet and every page of every notebook. Even the black tome with the sheets dipped in ink not a spot of white nothing whatsoever to read. The submerged grasped that Ari was not always a destroyer of language; he had, in some lost history, been the opposite. Something had changed and lay hidden within the pages.

She finally came upon it, one sheet partially salvaged, in the back of a leather bound volume, the most regal of the collection. The Kings passage reversed ending with the vertical eye in the triangle. Julianne did not have to read the excerpt to comprehend. Her eyes widened, wide as they could, petrified, glistening at the edges, moistening with tears. The eye stared at her, its iris flaring up, the beacon she sought, that elevated force more perfect than the beings from which it borrowed its outlines, that which directly perceived and absorbed all, transmuting it into coal-colored flames, burning with the fuel of perception, more direct and immediate than the text that hugged it on all sides, it wanted her to know what he didn't, her to be privy as a small recompense for the mishap of blood, her the accidental victim and he the usurper of its grand vision, and so she looking into it, transfixed, knew what he had considered but had not realized fully, though she could not possibly know this, it was truly logically impossible for her to know this: that the dial of Ahaz was improperly constructed, the story indeed amounted to nothing more than myth, titillating but vacuous, Ari's belief in a collective imaginative faculty willing its mythology into reality false, the factual basis for the mechanism distorted, the mechanism enabled gone awry and so too the trinity of bodies within its scope, and so not reversal, not the intended reunion and reconciliation, but instead sighs and whimpers, only sighs and whimpers, forever sighs and whimpers, until those too would disperse.

I

The suggestion of a breeze trickled in through the windows of the study. Rays of summer light reached inward and struck Julianne's desk in direct, linear strokes. From the source to the receiver, as one would expect. They fell upon a stack of cerulean hardcover books, each a discrete iteration of a single work entitled Flights and Follies. Below the title shined the name Julianne Porter, and the underside obscured a serious but pleasant photograph of the young author.

Across the next room, the door unlatched and the illustrious woman in question stepped inside.

She placed her keys on the hook by the door and removed her blazer with one motion, hanging it on the coat rack. After crossing into the study, she seated herself at the desk and released a condensed sigh. Her eyes fell upon the book stack, much like the rays of daylight before her. Straight lines from the eyes of the sun and the woman converged at the same spot from their respective focal points. Upon converging, the narrow lines rebounded, returning to their sources, transmitting the knowledge to both minds. Julianne smiled with pride, and the slightest hint of vanity appropriate for a person so youthful and grand.

Catching herself in this brief moment, Julianne opened her laptop and began perusing the day's emails. A series of congratulatory messages greeted her, from friends and acquaintances of all sectors of life. She had acclimated to these effusive outbursts and the associated sensations of embarrassment were beginning to subside. She would respond to each later, adding the new group to yesterday's backlog. After closing her laptop, Julianne retrieved an envelope that lay within the top drawer. Handwritten in the man's eccentric, nearly inscrutable script, the letter, from its fond address to Jules and throughout its tailored, specific reaffirmations to her character, substantially augmented her long-awaited sense of achievement. Ari, whose name sealed the close of the contents, was not one for whom such words came readily or frequently. Julianne slipped the letter back into its place and resolved herself to the cult of forward motion.

→ → →

Miss Hudson leaned forward from the green couch and towards the coffee table. Sunlight and dust had washed out the fabric and made it a sickly khaki color, one that engulfed her as her weight sunk into the mold of her bottom, a mold decades in the making. She shifted slowly through the array of photographs on the table, one after the other, sorted perfectly and neurotically by the date in which they were taken.

Three such photographs were deemed the most crucial for the succinct efficiency in which they encapsulated a life. A boy with black hair and bright eyes tightly clutching a yellow puppy in his arms like the most precious of infants. The same boy with another, with lighter hair; this other boy expressionless while the black-haired one beamed profusely. And one of herself, with the child from the other two, flanked by a man whose eyes caught something outside the frame at the last moment. The images all belonged to the same period of the boy's life; in them all he stood ready, vital, and unaltered. Miss Hudson looked at her younger self at his side and caressed each with a lingering finger. With a pair of scissors, she carefully excised herself from the photograph. This she did in every scrapbook; each one a wholesome conglomeration of images with the occasional ghost looming in the background, its figure expunged from the composition because it was deemed unworthy, it was not a complete being, it had attempted to engage the masses around it but this attempt went unreciprocated, he and he and the masses and they would not be her stalwarts, her beacon or her patrimony, they would not so she could not and so she would slip inwards and backwards, the memory would be altered, only those in essential existence allowed to have a presence. Miss Hudson slumped deeper into the couch. Her gaze blurred in and out of focus, from crisp strokes of vision to a uniformed periphery and back. She would make this scrapbook for her son, and slide it tenderly atop the others.

→ → →

And he made darkness pavilions round about him, dark waters, and thick clouds of the skies. The eyes scanned left to right, down, left to right, down. Move and shift and move and shift and do not look away just yet. The piles of texts on Ari's left would have them think his was a religious studies dissertation. And while they were invaluable for the context, the truly vital tome was much newer and quicker to read. It sat beside his notebook, a desperate thing filled with those trademark inscrutable scribbles, the only volume not from the aisles surrounding him, obtained rather surreptitiously. An unfinished work, the small leather-bound book lay heavily in its own enshrined austerity. Why was it unfinished? It needn't be, it needn't be. But Ari could only peer inside when he was certain no passersby approached his sequestered den on the top floor.

The connection between each side of the desk was clear, the dichotomy split evenly by his notebook: ay, he would let the shadow return backward ten degrees. It was no light thing. And that was what, but how? The small leather book provided the knowledge, but its author had only arrived at conditional and not actual truths. Ari found himself clutching a lantern in the outskirts of a primordial woodland. The lantern had taken years to discover, both in its object and operations. All that remained was the exactitude of steps, the lefts and rights and directional flourishes of toes forward and diagonal towards the beacon beyond the trees, luminous but obscured by trunks and undergrowth. And so Ari reread the texts and scribbled frantically in his notebook, pulsating with the thunderous ache in knuckles and synapses that would finally seize the vigor of he who rides on clouds.

No one would expect Ari Hudson's apartment to be any different from the way it was. Everything meticulously stacked by subject atop the desk, or filed away in drawers below. Writing utensils grouped by color and type in their respective holders. Walls barren and sterile because knowledge had been contained, ushered into hidden pockets and clandestine volumes. His mother had tried to inject décor through her trademark photo collages. Much to her dismay, however, he hung these only in unfrequented corners. Ari had appreciated the sentiment but found them clunky and overbearing in their hyper-nostalgia: a mere glance at Lucas or his old puppy would immediately reinvigorate the despondency that sat like a rough-hewn tar chunk in his gut. Luke. He found it a curious matter that the two of them, so deeply bisected at odd ends of experience, could then coalesce at the same locus of misery. A rough-hewn chunk in his gut. His writings and books did not make him feel this way, and so it was these that he hunched over at his desk.

The hanging lamp kept the shadows at bay. The link was clear; now for the particular movements. And Isaiah the prophet cried unto the Lord: and he brought the shadow ten degrees backward, by which it had gone down in the dial of Ahaz. Ari wrote the excerpt from left to right. But this was merely a starting point. Though his aim was not unlike theirs, he would not trace the steps of the disciples. Form would follow function. And so below he wrote the inverse. zahA fo laid eht ni nwod enog dah ti hcihw yb, drawkcab seerged net wodahs eht thguorb eh dna: droL eht otnu deirc tehporp eht haiasI dnA. This would not suffice, as Ari had expected. He was still writing from the top down, and why? Merely because that is what one does. And why?

The inverse again, this time from the bottom upward. Ari had foreseen this failing as well, but he was working through the steps to slowly dismantle the paper's sense of convention. Though no longer going from left to right, the origin remained stubbornly on the left. From the bottom right and up, then, and again in columns until the top left corner. But why use a rectangle at all? Form must follow function. Man's disobedience was crucial, and Ari was almost there. He had pushed the branches aside and was standing directly in front of the beacon. It still shone a heavenly glow. He would touch it and it would change, reform its flame to shades of obsidian. But he would need more than knowledge entwined with defiance to do so. Ari left enough space for one more character in the center of the page. He would shift to the appropriate shape when necessary.

The process, as far as he understood it, was succinctly thus: first, desynchronization, then reconstruction of the temporal elements in the desired arrangement. Desynchronization the stripping away the divorcing of each human body from its knowledge and identity. Once divorced the parts could be reassembled as necessary. His reconstruction would be a reversal, wherein the predominant ethos of each would return to a prior form, untainted by the entropy that had gnawed them all down over the years and placed them at odd angles of the triangle without hope for convergence.

He realized, without fear, that one portion of the process could succeed, while the other could suffer complications. Everything out of synch and only disarray. Things worse than they were before, though they seemed unbearably low at present and he could not fathom a suffering beyond the present. Perhaps it was for that reason that no one had attempted it. Perhaps too they had regarded the Book of Kings as a mere myth. Ari certainly did, but thought that enough belief in something could—could—yield materialization, that perhaps a collective imagination, even in something so hopelessly ludicrous, would usher it into being in some weak but exploitable sense. And if the story had even a shred of truth to it through this collective ascription of significance, then it could be extracted and thrown on its head.

That was the theory anyway. A theory imagined through words, utilizing words, hoping to affect something beyond words. It had taken Ari ages to realize that erudition alone would not suffice. The black tome had hinted that one could get this far, then still be one step short. Ari was confident that his studies could help him bridge this final gap, but knew too that no amount of arcane letters alone would do so. He would step beyond what was formed and organized and proliferated and human, beyond and back into the primordial juices that charged and could recharge. An ignition image and blood. Sight and feeling utilized so that sight and feeling could be altered. Once he had the blood they would no longer be stuck. It was no light thing.

→ → →

Lucas tied off his left arm with his right. He needed to lay off the right for a while. The bruise peered back at him, an indigo glimpse into another galaxy. The sun had just set and he slumped on the couch amid the graying embers of remaining light. He had somehow convinced Julianne to join him the night before but tonight he would be alone. The little syringe he had provided for her sat next to his larger one. Lucas only gave her a small helping but she hadn't enjoyed herself. Her stomach had splintered and her head swam with nausea. It was too much. She wanted to experience all that life had to offer but not that. He had shrugged at her reaction, saying nothing until she left. She had given him one final, lingering glance. Then the door closed quietly, sound and movement synchronized.

Lucas applied pressure to the syringe. Lucas was the wooden frame around a flash of light, the parameters around something nebulous that had once began the process of burgeoning but was thwarted shortly after inception. The path had grown too dusty too soon and so he sank himself into the dust.

The agents that would have enabled him to do otherwise were not to be trusted. They were arrogant, pretentious, parading their masturbatory writings in the name of creation and scholarship. He hadn't congratulated either of them; not her for her novel, nor him for his various acclaimed theses and articles that were rapidly circulating every department. He read most of Flights and Follies but couldn't get past the first page of any of Ari's theoretical treatises. Their works were heaps of words heaps of letters heaps of lines marks scrapes and nothing more. The last true feelings were scratched vaguely onto cave walls centuries ago. Everything else was merely another layer atop the systematized construction of human endeavors, a massive, inorganic pile of floating space expanding infinitely only to strengthen and extend ephemeral institutions. Lucas applied more pressure to the syringe, exhaled. He would evade their trap and take a detour. He would not permit mankind to obstruct the direct and immediate flow of one spark to another.

→ → →

Ari was still standing in front of the beacon and it was still heavenly but it wouldn't be soon and in the wake of this he grinned. In moments it would meet his fingers and he would be healed like Hezekiah before him. Only he would achieve it himself, without the need for Abraham or any other being. In the attic, the necessary components sat before him. Their acquisition proved supremely difficult both physically and psychologically. Ari had gone into the country and purchased the goat from a jovial farmer who assured him her mother had been as strong and reliable as they came. He had drugged the infant beast and placed it in a potato sack just outside the coal outline of the triangle, under the table in a small tub. He couldn't bear to look at it for the time being.

Ari's second source of internal contention had to do with his mother, whom he had visited earlier that evening. It was the first time in over a year and her stagnancy seemed to subside for an hour while they reunited over tea. While she prepared the biscotti on an elegant silver tray in the kitchen, Ari dropped and stirred three Ambien capsules in her cup until they dissolved. She remarked that the tea was not as good as she remembered and apologized repeatedly. After she had fallen asleep, Ari slipped a needle in and drew a small volume of blood from her arm. It pained him to do it and he had would have preferred a more subtle method but it would not hurt her and even if it did it would not matter once the dial was set back. She would wake up groggy and perturbed the next morning but it would not matter once the dial was set back.

The three vials lay on the table next to the knife, the brush, the torn sheet of paper from the notebook, and the black tome. The other vials were easy to procure both literally and psychologically; one was his, the other Luke's. Ari had found his living room window ajar. His old friend had been unconscious on the couch with a large needle sticking out of his arm, and so Ari took the smaller one on the table nearby, filled with blood from what looked like the night before, before heading out through the window. He deemed the theft doubly warranted: firstly, there was no shame in removing a tool that would only harm a junkie. More importantly, Luke was sure to benefit greatly from the experiment as he would get a second chance at everything.

And so would they all. The researchers before him were daunted by the radius of effect they needed to invoke. They had been too ambitious. They wanted the dial back for everyone, for the world itself, as conventional desires had dictated for ages. Ari would greatly limit the scope and thereby ensure its success. The secret was in three, not in infinite, points. His aim was not a lofty or lustful one. It was for himself and his loved ones alone, and even then only the troubled ones on the brink of absolute despair. What he had to do was unpleasant but it had to be done. If it could be, if all the volumes of texts and endless ruminations accumulated to this evening, why shouldn't he reach forth to reach back? Even if the energy he needed to invoke was vile, why shouldn't he reach forth to reach back?

Ari stepped forth and took the blade in his hand. He was not proud of what was coming but expiated all reservations from his skull for the sake of precision. He hunched under the table and lifted the heavy potato sack. He removed the small goat from the sack and placed it into the tub, forced the blade into its virgin heart. The fur matted as its life ebbed out. The beast did not cry or awaken. Ari pulled out the blade and let the carcass drain and pool into the base of the tub. With the brush he painted over the outline of the triangle with the blood, beginning from the bottom angle and moving clockwise until he met the starting point. He then copied the excerpt from the notebook, dipping his fingers in the tub and painting the letters inside the triangle, following its outlines from the bottom and counterclockwise until the center. He left enough space only for the ignition image, a vertical eye whose composition would be human and not beast. This he painted in the vacant space in the very center, first with his blood, then a second and third coat with his mother's and Luke's. A small volume remained in each vial, which he smashed onto each corner of the triangle in the same order. The glass shards glistened at each point and Ari's hands bled afresh.

Each step had been executed slowly, deliberately, with the careful exactitude of a man whose craft had been years in the making. With the final vial shattered it was complete. Ari stood up at the base of the inverted triangle and stared directly into the crimson eye at its heart. It returned his stare. Its outline thickened and pushed outward in every direction, pulsating with the juices of its subjects. The beacon was lit and flared up, the flames flickering the color of coal. Some sort of regress was imminent. In the attic, the great eye widened and widened.

↓ ↑ ↓

selected literary criticism & music journalism

Navid Ebrahimzadeh

[1] Introduction: Situating the Critical Discourse Surrounding Waste

A paradoxical and porous category, waste presents a series of cultural conundrums: simultaneously repulsive and attractive, ubiquitous and invisible, utterly necessary yet, by definition, valueless. Whether in the form of material waste or refuse, bodily waste and excretions, social waste (sometimes wasted, and more often than not deemed wastes of space) and the places they inhabit, these subjects, objects, and spaces are considered extraneous and inessential, a waste of time itself to ponder, when considered at all. Yet waste starts to turn up everywhere the moment we look for it, the everyday castoffs of the various economies that we participate in, and in which we are inescapably embedded. There is, in fact, a quiet but long-standing history of literature and art fixating on waste as the thematic, formal, or social centerpiece, the subject matter, the aesthetic principle, or in some other capacity, the very ethos of the work. What purpose or purposes could an artwork centered on waste, an aesthetics of trashiness, possibly serve? How does art respond to and work towards the production of paradigm shifts in the history of trashmaking? How might these castoffs signal back, tellingly, to the economies which birthed them, and where else might they signal?

This dissertation seeks to examine waste in its literary forms, primarily but not exclusively as represented by twentieth-century American prose writers, as they develop alongside the institutionalization of private and municipal waste management and a consumer culture increasingly divorced from the stewardship of objects. First popularized in literary modernism and cultural studies in Charles Baudelaire’s mid-nineteenth century landmark work Les Fleurs du Mal (1857), and later excavated in Walter Benjamin’s 1930s writings on Baudelaire, the interrelated topics of waste and trash, waste’s most omnipresent manifestation, have since grown exponentially, becoming a discourse unto themselves. From 2014 to 2016, a series of critical works across the disciplines of literary and cultural studies, philosophy, environmental studies, urban planning, and sociology (Viney 2014, Bozcagli 2015, Morrison 2015, Rania and Jazairy 2015, Alworth 2016, Dini 2016) have focalized waste as an increasingly pressing and dynamically flexible rubric for excavating the discarded elements of modern literature and culture. In this way, the study of waste often serves as recovery work: trash gets swept aside, trashy literature unflinchingly centers it, and literary, social, and urban garbologists extend that centering.

While this dissertation focuses on twentieth-century U.S. prose, these texts cannot be fully understood without some recourse to foundational texts produced in nineteenth-century European literature. Charles Baudelaire and Oscar Wilde, two important apologists for trash and uselessness respectively, establish a contrarian ethos and aesthetics which the next century of waste-oriented literature, by scrutinizing the lowly and abhorrent, generally retains. Les Fleurs du Mal, Baudelaire’s decadent scrutiny of urban and erotic experience, opens by announcing to its appalled audience that its principle aim is to “find charms” in the “most repugnant objects. His poem “The Little Old Women” maliciously addresses the newly developed urbanite, who “trudge[s] on, stoic … / through the chaotic city’s teeming waste” (Baudelaire, IV, 1-2). In marked defiance to this apathetic figure, Baudelaire suggests that the urban poet must immerse himself completely in this ignored refuse material, directly and with a morbid tenderness. In poems such as “To a Red Haired Beggar Girl,” he extends this poetic attention and sympathy to the socially discarded, though no poem encapsulates this ethos as thoroughly as “The Ragpicker’s Wine,” wherein the ragpicker moves through the Paris, here termed a “muddy labyrinth” collecting “the dregs, the vomit of this teeming town,” in direct relation to what Baudelaire considered the poet’s task: to engage wholecloth the city’s discards in lieu of myopically or hypocritically denying their existence whatsoever (4, 16). Walter Benjamin drives this point home in his 1938 essay “Paris of the Second Empire in Baudelaire”: The poet’s task is to locate his “heroic subject from this very refuse,” to serve as a counterweight to the masses of ordinary citizens who fail to see it (108). As opposed to the Romantic subject whose engaged aesthetic is nature, the modern poet considers, in the words of Bill Brown, “the detritus of culture” his “fully engaging aesthetic object” (11).

Alongside the figure of the ragpicker, fin-de-siècle aestheticism works to instantiate alternative systems of value that twentieth-century art continues, complicates, and rejects. “All art is quite useless,” declares the infamous preface to Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890), and it is precisely this uselessness which is to be cherished, not bemoaned (xxiv). The aestheticists demand an autonomy of art from other intersecting manmade institutions—political, economic, and moral—seeking a prized sphere of production not tethered to the vulgar and literal-minded pragmatism of the marketplace or Victorian didacticism. Uselessness becomes the standard by which art is judged because usefulness serves as that standard for the majority of other discourses and practices. Here we see an early and influential initiator of an alternate and contrarian economy of value, one which confers value onto valuelessness largely due to its negative assignation by the dominant order of the historical moment. In the interwar period of the next century, this inverted aesthetic hierarchy is taken up by Virginia Woolf, whom Douglas Mao dubs “an inheritor of those rebellions in which the aesthetes and decadents pitted a doctrine of beauty as terminal value against the renowned Victorian tendency to stress art’s powers of moral instruction” (29).

In aggressive contrast to the nonobjective and aesthetically autonomous aims of early abstract art, the avant-gardes of Dada and surrealism—in particular the readymades and the surrealist found objects of Marcel Duchamp and Man Ray in the mid-1910s through the 1930s—highlight the contingency, rather than the autonomy, of the art-object in particular and the institution of art altogether. This is sometimes achieved through the use of trashy or lowly objects, in part because such materials make the supposed disparity between art and non-art most immediately and jarringly apparent. More broadly, however, this is performed through the historical avant-garde’s attempted fusion of art with the quotidian, the material manifestation of everyday life as a countermeasure to aestheticism’s dissociation from “the life praxis of men” (Bürger, 48).

The foregoing proto-modernist and avant-garde explorations of the undesirable, the overlooked, and the displaced speak to the relationship between waste studies and Anglo-American modernisms. In the eyes of the urban majority, trash—a ubiquitous, worn-out element of experience stripped of its commercially appealing, visually dazzling appearance—is designated as banal. Trash and other banal objects are seemingly inappropriate subjects for mimetic representation, yet modern art repeatedly focalizes and renders them both visible and significant, whether due to their intrinsic or potentially transcendental properties. Duchamp’s radical interventions play an essential role in this abrupt and jarring switch. While a readymade is not a piece of trash or even a form of waste—after all, a bicycle wheel, urinal, or comb, modified though more or less intact, still retains some glimmer of functional use or exchange-value—the way in which the readymade is repeatedly dislocated from one network of value and reinscribed in other, purportedly mutually exclusive networks, functions in parallel fashion to trash-centered art. For it is the artist’s surprising and even shocking choice of debased, lowly, or quotidian subject matter and materials—in Thierry de Duve’s formulation developed from Michel Foucault, the enunciative function which states “This [lowly rubbish] is art”—which is responsible for the object’s passage into the aesthetic realm (98). By puncturing the plenum of each previously sequestered domain and re-situating their contents, such a passage fundamentally uproots the foundations of both systems thereafter (98).

“The Lowly Remains” is informed by a wide array of critics, functioning in part to survey influential scholars in the field as starting points for cultural excavation. It is a critical commonplace for scholars of waste to begin with cultural anthropologist Mary Douglas. Indeed, nearly every book on the topic—Gay Hawkins’ The Ethics of Waste (2005), William Viney’s Waste: A Philosophy of Things (2014), Zygmunt Bauman’s Wasted Lives (2005), David Pike’s Subterranean Cities (2005), Susan Morrison’s The Literature of Waste (2015), David Alworth’s Site Reading (2016)—opens with a discussion of Douglas’s analysis of polluting behaviors in Purity and Danger: An Analysis of Concepts of Pollution and Taboo (1966), the landmark work in structuralist anthropology which might be considered the ur-text of what this dissertation terms “trash studies,” the literary and sociological extension of the overlapping fields of garbology and archaeology. Mary Douglas famously defines dirt as “matter out of place” (45). Her examples illustrate how cultural concepts of pollution rest upon spatial context and a violation of the ordering principles entailed therein: shoes, for instance, “are not dirty in themselves, but it is dirty to place them on the dining-table; food is not dirty in itself, but it is dirty to leave cooking utensils in the bedroom, or food bespattered on clothing” (45). If, then, dirt is “dirty” in a bed but not in a garden, then what makes dirt problematic is not its material fibers, but its violation of categories and its penetration of borders regulated by complex rituals which keep polluting behaviors and objects at bay.

Recent scholars such as Martha Nussbaum and William Viney have challenged Douglas’s ideas, including her radical stance on relative structures of difference or her over-emphasis on place rather than time. Hiding from Humanity: Disgust, Shame, and the Law, Nussbaum’s 2004 study reconsidering contemporary U.S. obscenity laws, criticizes Douglas for defining impurity almost exclusively in terms of spatial anomalies. Nussbaum notes that there are anomalies that do not elicit fear or disgust, suggesting there is more to the phenomenon than its contextual outlier status. The example she uses is a dolphin—as sea-dwelling mammals, dolphins violate biological and spatial borders but are not viewed as dirty or contaminating (Nussbaum, 91). In Waste: A Philosophy of Things (2014), William Viney challenges Douglas’s emphasis on matter out of place, opting instead for an emphasis on matter out of time, given that notions of inutility and uselessness operate not merely in a spatial but also in a temporal framework. Because it is tied not only to where it is and is not, but when it has and has not been, waste is “both inert and mobile, in and out of place” (Viney, 112).

Despite these criticisms, most work in the field is coextensive with Douglas, applying the porous boundaries of dirt and cleanliness to other spheres, such as urban space, literary taste, and bodily contact. Douglas’s assertion that dirt is a contingent rather than necessary substance opened the doors for scholarship to consider multiple forms of undesirable detritus in the context of social practice—that waste matter can be “read,” and that such readings reveal that waste is context-dependent, ultimately working to unsettle the borders between private and public, between cleanliness and trashiness, and between the categories that order space itself.

Douglas’s account, then, provides an intriguing and flexible rubric for examining various discarded elements of modern culture. If cleanliness must eliminate trashiness, the identity of which is predicated on its expulsion from “a systematic ordering and classification of matter,” then trashy literature and art poses a radical potential for disordering basic categories, be they related to commodity production and fetishism, literary aesthetic values, border-averse emotions such as fear and disgust, or the ordering of matter in the form of urban planning, to name a few applications pertinent to our inquiry (Douglas, 45). Trash writers and scholars have used Douglas’s basic assertion—that waste is contingent, legible and culturally informative—to ends as diverse as these, some of which will now be outlined, before we eventually turn to alternate methodological starting points and limitations.

While matter is classified along lines of pollution and cleanliness in every epoch and culture, where those lines are drawn and which principles they enact varies greatly. The particularities of modern regulatory practices and attitudes towards the production of goods and the excesses they create must therefore be attended to at some length—specifically, the transition to a modern Anglo-American consumer culture intent on efficient production, a paradigm shift which constitutes the historical backdrop of the dissertation’s first chapter on corporate waste. Alongside Douglas, the work of this dissertation is heavily indebted here to American historian Susan Strasser and French structural anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss, whose contributions to the field will now be summarized.

Strasser’s Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash (1999) details the many minute transitions in the means of production in the nineteenth- and twentieth- century U.S. and the corresponding social attitudes towards possessions and refuse—and, more crucially, how objects progressively slide from one category to the other at faster rates over time. In examining a wide range of primary documents including domestic advice books, household and factory inventory lists, sanitation policies, reform efforts, and trade journals, Strasser produces a taxonomy of common goods and their increasingly public, rather than domestic, production. Here, Waste and Want echoes the now well-documented transition from agrarian to industrial capitalism, wherein the production of basic necessities shifts primarily from the home to the factory, from within the household to without. Prior to this transition, customers “practiced habits of reuse that had prevailed in agricultural communities” (Strasser, 12), including boiling food scraps into soup or feeding them to livestock, taking worn-out items and clothes to their makers or mending them one’s self, reusing grease for cooking or to craft candles or soap, repurposing worn objects as toys, or burning them to heat rooms and cook (Strasser, 30).

Strasser’s text utilizes Lévi-Strauss’s concept of bricolage, one central to this dissertation, to illustrate the fundamental paradigm shift in the modern history of trash. In The Savage Mind (1962), Lévi-Strauss defines the bricoleur as “someone who works with his hands and uses devious means compared to those of a craftsman” (16-17). The bricoleur does not limit his materials to the conventionally received set—the “materials and tools conceived of and procured for the purposes of the project”—opting instead for “whatever is at hand” from a wide and “heterogeneous repertoire” (Lévi-Strauss, 17). This odd-job man thus exhibits a synergy, rather than a divide, “between the toolbox and the junkbox,” or, in its gendered nineteenth-century equivalent, the sewing kit and the scrapbox (Strasser, 11). The rise of factory production, by contrast, widens this divide. Whereas nearly “everyone was a bricoleur in the preindustrial household of the American colonies and, later, on the frontier” (Strasser, 22), as the site of production shifts outside domestic space, the general populace’s “kinesthetic knowledge of materials” wanes (Strasser, 11). More and more, fewer people can mend worn-out objects and feel a decreased sense of responsibility and proximity towards those objects, as what was once a necessity becomes a superfluous hobby. This, in tandem with an increasing emphasis on convenience and speed, marks the gradual move towards a fledgling interwar consumer culture—emphases which, as will be demonstrated, expand significantly in the postwar era.

The shift to modern consumerism entailed, then, not merely a change in where commodities originate, but in who possessed and continuously practiced the tactile skills to produce, evaluate, and repair them—not merely a shift in the social organization of producers or their attitudes towards equipment and nourishment, but the range of technical abilities upon which those attitudes rest. From the standpoint of the unskilled or underskilled user, the object’s period of usefulness is truncated more and more, its range of life at that node of its circulation lessened. As obsolescence occurs much earlier in an object’s life cycle in contemporary history than ever before, discarded objects become more and more materially present and conceptually pressing. As will be illustrated, trashy literature and art often opts precisely for these bricoles—the odds and ends jettisoned from dominant economies of value—in part as an effort to bring them into an alternative system of circulation with wider and less rigidly utilitarian and pragmatic parameters than those held by the factory or average consumer.

Systematic practices thus arise in turn to meet and form the demands of a consumer culture whose relationships to objects becomes increasingly transient and atomized. Much as the expulsion of dirt defines purity, capitalist models of mass production are predicated on the expulsion or mitigation of inefficiency, of useless matter and wasted energy. In this vein, cultural critics Anson Rabinbach, Mark Seltzer, and Elspeth Brown examine the paradigm shift that arises in the development of Western industrial capitalism deemed the productivist model of efficiency. Rabinbach’s The Human Motor (1990), a detailed study of the relationship between nineteenth-century European scientific discourses and the development of the fully-fledged bureaucracy of industrial capitalism, defines “modern productivism” as “the belief that human society and nature are linked by the primacy and identity of all productive activity, whether of laborers, machines, or of natural forces” (3). Emerging scientific discourses analyzing the release and containment of energy, such as thermodynamics, form the basis for a factory model which unites modern subjects in the establishment of values pertaining to speed, efficiency, and the reduction or elimination of waste. Rabinbach looks at the emergence of conceptions of fatigue and neurasthenia in nineteenth-century science, which take on central importance in Western culture in the 1870s and beyond. This manifests as a “widespread fear that the energy of mind and body was dissipating under the strain of modernity,” with increasing attention afforded to “the need to conserve and restrict the waste and misuse of the body’s unique capital—its labor power” (Rabinbach, 6).

As we will see again in waste discourse, waste is aligned with, and often defined through, fear: the fear of wasted energy, objects, subjects, and spaces alike, and the violation of dominant principles and borders that this entails. Seltzer’s Bodies and Machines (1992) and Brown’s The Corporate Eye (2005) extend Rabinbach’s analysis (Brown’s explicitly stated purpose is to apply Rabinbach’s European framework to corporate American visual culture), noting that this paradigm shift entails a rethinking of the human body as a mechanism whose inevitable waste products must be controlled in the name of orderly production. Seltzer notes that “bodies and persons are things that can be made,” and that the “conversion of bodies into living diagrams” allows for a transcendence of their limitations through both scientific and ideological management (3, 160). In turn, Brown considers the manner in which photography was put to use in American corporate culture precisely through the diagramming that Seltzer observes—that the advent of photography made it such that bodily movement “could be frozen, broken down, and reassembled into a more efficient combination of individual movements,” which in turn could be used to instantiate the ideal “subjective relationships to the workplace and to finished goods” in the name of a highly programmatic direction of energy into maximum efficiency with zero waste (4). In their discussions of productivism, Rabinbach, Seltzer, and Brown take up early sociologist Max Weber’s concept of rationalization, defined in The Protestant Ethic and the Spirit of Capitalism (1905) as the secular reorganization of “economic life, of technique, of scientific research, of military, of law and administration” around the principle of efficiency rather than religious belief (26). As with productivism, the facet of rationalization specifically concerned with labor, rationalization substitutes efficiency for “magic as a means to salvation” (Weber, 117).

Both the fear of waste and the quasi-metaphysical belief in production as the prime mover of nature and industry alike are epitomized in Henry Ford’s My Life and Work (1922). The specter of waste looms over the industrialist’s autobiography; indeed, it is anathema to Ford, appearing on nearly every page as a deplorable and unnecessary condition of the status quo. The opening passage excoriates the contemporary factory model for encouraging workers to “waste so much time and energy” and therefore lose the “full return from service” as a result (Ford, 2). In criticizing agrarian labor methods, Ford identifies “waste motion—waste effort” as the culprit for high overhead and low profits (15). Elsewhere he identifies ignorance as the culprit for waste in its many iterations: “Waste is due largely to not understanding what one does, or being careless in the doing of it” (Ford, 19). Waste aversion culminates in detailed rationalization as a scientific and technocratic antidote when Ford calculates that reducing ten steps a day per each of his employees would result in saving “fifty miles of wasted motion and misspent energy” (77). Wastes of space are also targeted, as he details the measurements required to give each worker the exact amount of room to operate his machinery: though the workstations “may seem piled right on top of one another,” they are in fact “scientifically arranged” according to this principle, so as not to squander an inch (Ford, 113). Since the industrialist exhibits “a horror of waste” both “in material” and “in men,” the onus rests on him as manager and arbiter to strategize and implement the appropriate regulatory methods to combat this horror (Ford, 16). The essentialist rhetoric of intrinsic horrors and aversions that every industrialist exhibits here closely echoes Thorstein Veblen’s discussion of humanity’s inborn appreciation of efficiency in The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), wherein he states that man “is possessed of a taste for effective work, and a distaste for futile effort. He has a sense of the merit of serviceability or efficiency and of the demerit of futility, waste, or incapacity” (15).

Time, energy, materials, motion, space, and men: all can be wasted under careless management, yet all can be salvaged through calculated, scientific arrangement. While Ford’s immediate inquiry concerns the manufacture of automobiles, the parallels to theological salvation narratives are clear, as Weber and Rabinbach have noted. Ford himself expands the reach of productivism to moral and metaphysical domains, for instance, when he vehemently states that “nothing is more abhorrent than a life of ease” and that “there is no place in civilization for the idler,” directly echoing Christian intolerance of sloth as well as its value-laden rhetoric, or when he expands the range of his postulations to “the largest application,” insisting they “have nothing peculiarly to do with motor cars or tractors but form something in the nature of a universal code” (13, 3). Under productivism, the principles of mechanical production are not specific to industrial capitalism but extend to all worldly registers, guiding and animating matter itself.

Certainly, attempts to minimize the wasted energy of labor efforts are not unique to modernity, though the scale to which they were rigorously theorized and implemented in these decades was unprecedented. While Fordism is the most well-known of these systems, it relied on foundational precepts inherited from Taylorism, so named for American engineer Frederick Winslow Taylor. At the turn of the century and through the 1910s, Taylor instantiated the system of scientific management expanded and transformed by Ford. In our history of corporate mechanisms undergirding waste production, as well as the transition from steward to consumer culture, the transition from Taylorism to Fordism is worth attending to here. Martha Banta’s history of this transition in Taylored Lives (1993) corroborates Ford’s own comments on the expansion of productivism beyond the realm of the factory. Whereas Taylor “had concentrated upon the man as laborer,” he paid “no attention to the house environment to which the scientifically managed worker returned at night” (Banta, 215). By contrast, Fordism “insisted upon the tight fit between laborer, citizen, and homeowner,” a tripartite structure aided by the establishment of the Ford Sociological Department, which provided varied benefits and assistance in procuring single-family housing (Banta, 215). Whereas Taylorism provided laborers with the minimum income necessary for subsistence and focused on the standardization of the labor process, Fordism instantiated a more pervasive model of production, consumption, and habitation by providing higher wages allowing for and normalizing commodity consumption and homeownership (Brown, 5).

Productivism and waste aversion therefore permeate well beyond the context of the factory or the public sphere, operating on domestic, moral, bodily, spatial, and social registers, as this dissertation seeks to demonstrate. Gay Hawkins’ The Ethics of Waste (2005), drawing upon Strasser’s historiography, shows how these principles extend into domestic space by means of a rhetoric oriented around convenience, noting that the production and marketing of more streamlined and packaged domestic products in the 1920s, whose aims were to prevent unnecessary domestic labor, brought “economic rhetoric about efficiency and streamlined production” into the household, thereby extending productivist principles and transforming the domestic sphere “into a site of fast, competent production” (26). American home economist and Taylorist Christine Frederick helped popularize these ideas through a series of articles in the Ladies’ Home Journal throughout the 1910s, as well as her book advocating domestic consumerism as part and parcel of a wider American ideal, Selling Mrs. Consumer (1929).

The logical extension of this ever-expanding discourse also manifests in Aldous Huxley’s Brave New World (1932), whose citizens move “steady as the wheels,” delighting in, above all else, “the principles of mass production at last applied to biology,” among other sectors (7). The novel’s dystopian application of Fordism satirizes modernity’s secular substitution of transcendental mysticism with overtly theological overtones. The majority of the novel’s characters, part of a labor force whose consciousness is homogenized in the name of efficiency, literally worship maximized production and hygiene, reciting Fordism’s hypnopaedic slogans such as “Cleanliness is next to Fordliness” and “History is bunk” or valueless (Huxley 91, 28). This latter aphorism, the aim of which is to lessen the parameters of understanding with respect to products and subjects alike, is telling in a waste-averse culture—one of the dissertation’s central arguments, detailed in the chapter summaries to follow, is that trashy literature aims to expand a historical understanding of objects not merely within, but beyond, the economies through which they circulate. As will be demonstrated, Viney is correct to assert that the practice of hiding waste matter spatially and ideologically also entails temporal consequences—when trash is only given serious consideration at the apex of its market value, its subsequent degraded forms are omitted or obscured from historical consciousness, as the consumer views only a narrow slice of processes of production, circulation, consumption, disposal, and reincorporation. It is also detrimental to the productivist machine itself, which paradoxically remains inefficient due to its wasteful jettisoning of materials; productivism aims to maximize market value while simultaneously narrowing the parameters of that value.

Thus far we have been attending to waste aversion, theorization, and implementation on the corporate scale, particularly the ascendancy of scientific management and rationalization under early twentieth-century American capitalism. While rationalization mitigates wasted motion and energy of the discrete laboring body, it does not explicitly probe the interior waste matters of that body. A second and slightly messier subcategory of waste studies analyzes the production of organic, rather than corporate, waste, on the anatomic level. Although the fear of wasted energy and materials mirrors the fear of debased human matter, the operating principle here is not efficiency, but disgust, having less to do with ideology and more with materiality. The corporate subject may disapprove of or discard trash, but it would be an exaggeration to say that it repulses him in the way bodily waste usually does. Alongside Douglas, the precursor here is Julia Kristeva’s influential definition of the abject presented in Powers of Horror (1982). The abject, neither subject nor object, draws the subject “towards the place where meaning collapses,” near but not beyond the margin of understanding (Kristeva, 2). It disturbs “identity, system, order,” and violates “borders, positions, rules,” attracting and repulsing the subject, threatening its radically contingent integrity, beckoning it towards a fatal destruction (Kristeva, 4). The parallels between Kristeva and Douglas are abundant, but for Kristeva the analysis revolves around a substance more debased than dirt: bodily excrement. “Excrement and its equivalents (decay, infection, disease, corpse, etc.)” present a fundamental “danger to identity that comes from without: the ego threatened by the non-ego, society threatened by its outside, life by death” (Kristeva, 71). While Kristeva’s account is primarily psychoanalytic and not anthropological (the abject reveals a traumatic separation from the maternal body into the ordered realm of the Symbolic), waste matter is once again coupled with unstable boundaries and the horrific fear of their undoing, a fear inextricably tied to our relationships to the undesirable. Along the same vein, Jesse Oak Taylor defines abjection as “the body’s reaction to its own matter out of place” (117). In other words, one way of conceiving Kristeva’s theory of abjection is by viewing it as a transposition of Douglas’s reading of dirt onto the human body; whereas Douglas considers “the sociocultural level of the social body,” Kristeva focalizes the individual body’s subjectivity and materiality (Taylor, 117).

Recent work in affect studies extending Douglas and Kristeva has sought to thoroughly define disgust, often through a taxonomy of disgusting objects, their effects on human psychology, and the ideological implications therein. Disgust is, according to affect scholars Colin McGinn and Carolyn Korsmeyer, primarily an aversion to two loathed facets of human reality: debased materiality and mortality. Disgust arises, in other words, when the human subject is reminded of the fleshiness and eventual decay of his or her body. McGinn’s The Meaning of Disgust (2011) analyzes disgust in terms of its tendency to elicit recoil: we turn away from the disgusting object in order to “preserve our disgust-free state of consciousness,” so as to “keep consciousness ‘clean’” (11). Korsmeyer echoes this directly in Savoring Disgust (2011), writing that disgust “erects a protective barrier between subject and object”—i.e. it rejects the subject’s proximity to the object in favor of distance (35). What is actually being kept “clean” is consciousness itself, not merely (and sometimes not at all) the body. Nevertheless, the content of such unacceptable ideas has to do with the corporeality of the body: blood, snot, and semen make it such that “our vaunted quasi-divinity dissolves into the mess of organic reality” (McGinn, 74). Bodily excretion revolts because it disturbs an anti-materialist idealism of transcending one’s flesh, an “ontological distance from our animal bodies” (McGinn, 74). Waste matter is, as we will continue to see, deemed better unseen, even as it flows dangerously beneath the surface.

Korsmeyer, returning to Kristeva’s theory of abjection, analyzes the disgust produced by proximity to corpses, arguing that “the ultimate recoil is from our own mortality” (35). Disgust arises when consciousness is threatened by contamination, with the central fear of losing “our bodily integrity,” which here means dying, decomposing, and becoming “the disgusting object itself” (Korsmeyer, 35). When it comes to bodily waste, then, fear is bound up with expulsion: not the expulsion of trash or of inefficiency, but of undesirable biological facets of lived human experience. Most interestingly for our purposes of examining trashy literature, perhaps, is the idea that such emotions arise indiscriminately in response to aesthetic and physical objects, or to representation and presentation alike. Korsmeyer notes that disgust has the capacity to “impart an intuitive, felt grasp of the significance of its object” in a fashion that other emotions do not—that the power of disgust informs the subject of the disgusting object with a sharp intensity (8). Disgust “achieves a direct and immediate arousal that penetrates the screen of mimesis or artistic rendition. That is, one recoils viscerally whether the object of disgust is aroused by art or by an object of life” (39). This idea, while dubious as thus boldly formulated, poses potentially radical consequences for the trash scholar, and maps onto a long-standing series of debates regarding the relationship of art and life and the challenges modern and postmodern art pose to classical conceptions of mimesis. If disgust overrides a suspension of disbelief in the reader, then disgusting literature has the potential to harness a potently disruptive aesthetic power, not merely a categorical or conceptual one, and one that allows for something akin to mimetic transparency, or, as will be argued in a later qualification of Korsmeyer’s assertion, semi-transparency. In the intermediary space between aesthetic and external reality, the literature of waste forces the experience of abjection onto the reader, but at one layer of removal, bringing abhorred objects back into focus in a way that physical interaction with them cannot.

Given the multitude of economies that function through the production and attempted elimination of waste, trash studies centers on a third and related subcategory: spatial waste, which shifts in both focus and scope from the corporeal to the industrial, from the microcosmic view of the body from within to the macrocosmic view of the city from below. The practices of urban planning, public sanitation, and urban renewal enact the concerns of a waste-averse culture on a grander scale through the attempted containment of undesirable populations, the construction of sewage and other streamlined waste disposal systems, and gentrification, respectively. In “Walking in the City,” the influential chapter on urbanism in The Practice of Everyday Life (1980), French philosopher Michel de Certeau follows the through-line inaugurated by Douglas and later taken up by Rabinbach and other scholars investigating rationalization of the body, analyzing the maintenance of polluting behaviors, bodies, and objects in the context of the modern metropolis. City planning, writes de Certeau, regulates and produces space by repressing “all the physical, mental and political pollutions that would compromise it” (94). Productivist civic administrations, utilizing the Fordist efficiency model of the factory, produce a regulatory taxonomy on a much grander scale—a classifying system of “differentiation and redistribution of the parts and functions of the city” which divides and orders subjects and objects according to its streamlined rubric (de Certeau, 94). That which cannot be organized and assimilated in this way then “constitutes the ‘waste products’ of a functionalist administration (abnormality, deviance, illness, death, etc.)” (de Certeau, 94).

The question that arises, then, is what to do—and what has been and continues to be done—with these seemingly unassimilable remainders? Beginning with de Certeau, Thomas Heise’s Urban Underworlds (2010) delineates the material, social, and ideological processes that produce undesirable zones of urban space and their inhabitants: how industrial capitalism produces rapid industrial expansion, which leads to population density, which in turn results in cultural clashes and the production of difference. Heise’s text then historically details the manners in which various industrial practices such as urban planning work to contain and regulate the resultant material and social waste to undesirable zones in the city out of “mandates for efficiency and legibility,” as well as sordid entertainment value in the form of slum tourism and the nightlife industry (95). The inhabitants of this underworld form the underclass—“the residuum that remains when all use-value is extracted from a given population”—which forms the basis of the following interrelated rubric on social waste (Heise, 54). In concert with Heise, David Pike’s Subterranean Cities (2005) examines how the image of the underground serves as a repository for socially deviant or undesirable populations in the urban imaginary: “alien urban categories,” including “ruins of things, places, people, and outmoded commodities” become pathologized and vilified before they are submerged and “metaphorically assimilated to the space of sewers” (3, 12).